This is the official web page and video of Citisense 2014. We are really proud of having helped and collaborated in making it possible.

http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/ict/brief/citisense

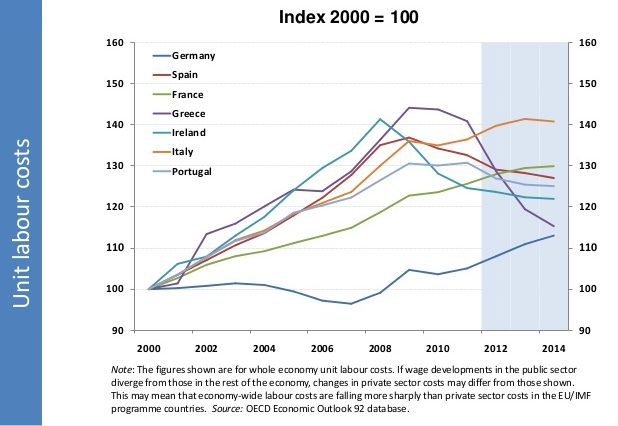

Hoy aparece en El País una entrevista a Ray Dalio, presidente de Bridgewater, el hedge fund más importante del mundo. Dalio hace un diagnóstico de la economía española de sobras conocido: trabajadores caros (51% más que en Estados Unidos), semana laboral sólo superior a la de Alemania y Francia, burocracia elevada, apenas un 4% de la población española es emprendedora (frente al doble de la americana) y por supuesto las dificultades burocráticas en establecer una empresa. ¿Suena familiar? ¡Seguro que sí !

Hoy aparece en El País una entrevista a Ray Dalio, presidente de Bridgewater, el hedge fund más importante del mundo. Dalio hace un diagnóstico de la economía española de sobras conocido: trabajadores caros (51% más que en Estados Unidos), semana laboral sólo superior a la de Alemania y Francia, burocracia elevada, apenas un 4% de la población española es emprendedora (frente al doble de la americana) y por supuesto las dificultades burocráticas en establecer una empresa. ¿Suena familiar? ¡Seguro que sí !

Paralelamente, estos días el Banco Central Europeo está empezando una política de Quantative Easing (QE) con la que Mario Draghi quiere captar la deuda de los estados europeos sacándola de manos de los bancos de manera que éstos den préstamos a las empresas en vez de aparcar el dinero en la deuda de los estados, un préstamo seguro y rentable.

Pero, ¿es ese el problema? ¿Todo eso va a solucionar los problemas del sur de Europa?

Ray Dalio decía que a España le iría bien una devaluación, puede ser, pero eso en el euro no es posible (aunque el QE inyectando euros va a provocar un descenso con respecto al dólar).

Todo parece ir fatal, sin embargo, si vamos al nivel de las empresas, vemos que hay algunas que funcionan muy bien: Inditex (Zara), Mango, Desigual y muchas otras tienen beneficios record y compiten a nivel mundial. No parece que tengan un problema de costes.

¿Qué es lo que pasa? ¿Por qué tenemos en el mismo país empresas que son lideres mundiales mientras el país está hundido en la miseria con un 23.7% de paro?

In early December I went to one of the few camera shops left in San Francisco, although I don’t live there I have bought cameras and lenses there many times (Discount Camera in Kearny – I love the place!). I was looking for a fix lens for my Olympus OMD-EM5, a 45mm and as usual, I ended up with a different model, a fantastic Leica lens. Throughout the buying process we were chatting about what had happened to camera shops. Can you guess how many are left? Only two downtown ! wow !

This is a familiar experience to all of us. Where is the photo-lab next door? And the record shop? How many hours did you spend browsing through vinyl’s first and CD’s later? They are all gone.

We normally say that Digital Photography killed Kodak, although in fact they invented it. But, what about the ecosystem? From photo-labs to photo-albums, a whole industry devoted to it has also gone.

Maybe the case of music is even better known and studied. It’s not only about the big record companies, but also the transformation of the business model and the whole ecosystem around it. Records and books used to take up a quite a lot of space at home. Now they are mostly decorative objects.

Many times when we think of disruptive technologies we think about the incumbents, the big companies that went from dominating the market to bankruptcy. But we don’t often remember the many jobs and business around the large companies that have been washed away by the tide of disruptive innovation. With them a myriad of jobs, companies and even competences got lost forever.

Will that be the case of 3D printing? Will 3D printing wipe out so many manufacturing jobs and will rock our economies?

3D printing started producing small pieces mad of resin. With time, this technology has become commonplace and now we can buy a 3D printer in a kit for $600. We realize to what extent this technology is being incorporate in our lives when we stumble upon one of these shops that produce a mini-you printed full-color in 3D for $100. Then, suddenly, we become aware that it is becoming mainstream.

However, not all technologies have the same transformative power. Some of them, radical and disruptive innovations can destroy economic empires, change our habits and create new meanings and social constructs in a matter of years. If you are not convinced of this, look into your pockets, what do you find there? A Nokia or a Blackberry? Chances are that you use an iPhone or Android based device. Only a few years ago these companies had market shares approaching 60% or 80%. Now, who do you know that uses a Nokia?

Is 3D printing one of this?

In many ways 3D printing as an innovation process resembles previous ones such as LCD TVs, PDAs (now called smartphones), … a pattern typical of disruptive innovation. A new technology appears that beginning as a toy, after a few iterations covers 70% of our needs with a huge price gap and eventually replaces and redefines a whole sector. This has been the case of LCD with CRT, SDD with hard drives or smartphones with mobile phones and so many other examples.

Always the puzzling story is that we know the outcome, we all know it. There is little doubt that eventually the old technology is going to be replaced. Looks this familiar? Do you think it fits well the pattern of 3D printing? Probably yes.

This is a quite old article that Henry Chesbrough and I wrote and got published in English on September 2014 due to the interest expressed by a large number of international delegations.

This is a quite old article that Henry Chesbrough and I wrote and got published in English on September 2014 due to the interest expressed by a large number of international delegations.

Our vision is changing, because Open Innovation is a moving field, particularly in the Public Sector and Smart Cities. However the one that we presented is still in many ways completely valid.

Here you can find the whole article and following the conclusions:

Innovation and cities are two concepts that have always gone hand in hand. Geoffrey West, who for many years was the director of the well-known Santa Fe Institute, has described the positive correlation between the size of cities and their innovation capacity in terms of a power-law (Bettencourt et al., 2007). That is, a city that is 10 times larg- er is 17 times more innovative, but a city that is 50 times big- ger is 130 times more innovative.

Large cities have always been considered places that welcome subcultures (Fischer, 1995) and non-conven- tional residents (Florida, 2005).

In this article, we have described the theory that the prevalent model of innovation in cities continues to be based on a structure of providing predefined services. This model does not include elements that enable cities to reinvent themselves, which is what is sought in smart city proposals (Florida, 2010).

The reinvention of cities, which should lead us closer to smart cities, requires the reinvention of the governance of cities themselves, particularly in terms of the manage- ment of innovation. This point is further supported if we consider the reality of cities as entities that compete for talent and creativity (Florida, 2008), in a world where competition is increasingly defined by the capacity to innovate, not just by efficiency or productivity.

In the article, we have focused particularly on inter- mediaries in innovation processes, particularly public intermediaries. We centred on a specific mechanism: the use of urban space as an area for research and experi- mentation by the citizens themselves through urban labs.

The existence of intermediaries is possibly one of the most relevant characteristics of open innovation process- es. However, although open innovation is prevalent in the private sector, it is only just beginning to be intro- duced in the private sector. Urban labs will definitely undergo considerable transformation in the coming years, and shape this new scenario of open innovation in the public field.

The need to become more competitive, or as expressed in other words “to grow”, has become an omnipresent topic in our society. Now, it is not only a topic of discussion in both the media and the public speeches but also a recurrent theme of debate in our companies, our professional life and even in our personal life. Spain is a country with 26% unemployment, with poor scores year after year on the Pisa assessment and who´s universities rank extremely low in world rankings. It could be said that the country has a major problem of compatibility.

It could be thought that in front of such dramatic panorama, the government would propose several new policies with the aim to flip the situation. However, it is clear that this is not the case, as a change has not been achieved. Even that it must be mentioned, that the desire to create change, nor the effort to diagnose and interpret the current problems, cannot be neglected from the existing implemented policies.

A few weeks ago, Risto Mejide (a well known publicist and public figure), interviewed Pablo Iglesias, the leader of Podemos –a raising left wing party in Spain-. The second one mentioned his proposal to create a minimum basic rent for everyone in Spain. At a point were both the viability and the details of the proposal are still unclear, what surprises isn’t the proposal itself –which clearly is not a new policy- but the interpretation of the consequences that implementing such policy could have.

Risto Mejide, highlighted two main issues in regards to the proposal. First, he remarked that it would be an extremely challenging policy to implement in times of crisis because the economic burden that it carries with it. Second, he mentioned that it would create an indolent publicly paid class. Arguments to which Pablo Iglesias curiously did not respond with social terms but with compatibility terms as he arguments that if workers enjoy a minimum basic rent they will not be force to accept the first job that comes across because their basic necessities will be cover. And consequently, companies will have to re-invent their business model to compete in more aspects than price.

From this simple proposal, two interpretations can be drawn upon the effects that it could have to Spanish society. But, can we know which one is true? Are Spaniards going to become indolent citizens living out of public money? Will this policy further reduce the national entrepreneurship spirit? Or vice versa, having a minimum salary guaranteed for everyone will allow Spain to become some sort of Silicon Valley as the number tech startups grows because the workers have the capacity to accept only those jobs that offer them a just compensation?

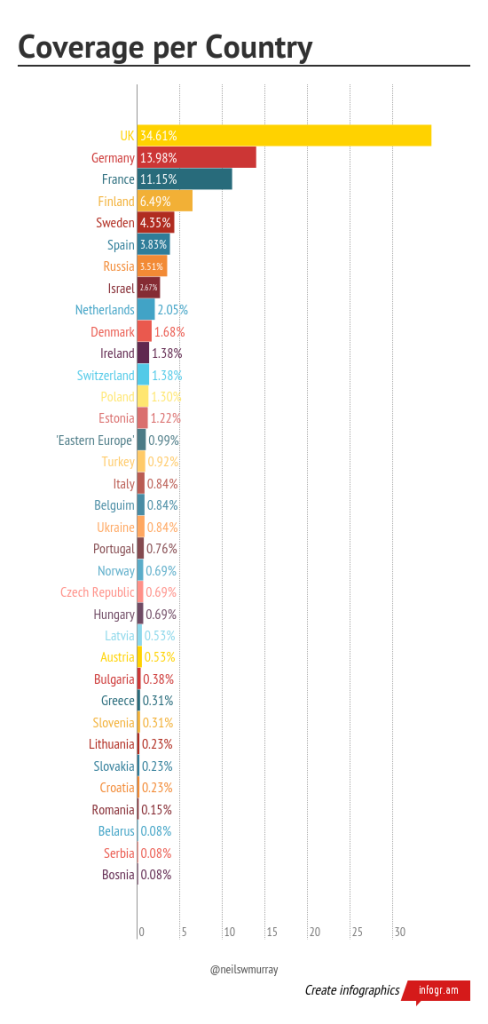

Neil Murrya @neilswmurray in Medium has explored the innovativeness of European countries from a different perspective. Instead of building a sophisticated index on the basis of theory, he compiled all the articles published in TechCrunch, The Next Web Europe and Tech.eu and distributed the articles mentioning concrete startups per country.

You can observe the result on your left.

Of course you can argue that TechCruch has a bias for UK because the main editor is from there and many of the editors are UK based. Being the biggest web of all three, UK could get a disproportionated attention that probably doesn’t reflect reality.

This is certainly the case because The Next Web was born in Amsterdam covering initially only Dutch startups while Tech.eu has an editorial stance of taking a wide European coverage.

Also, one has to correct also for events, which get a disproportionate amount of coverage. Slush in Finland, one of the hottest events in Europe where lots of venture capital is flowing is one of these cases.

By the way, this also shows the critical importance of locally rooted events as catalyzers of startups.